Happy Monday Morning!

Last week we penciled a newsletter titled Wildly Offside, in which we highlighted new research from the Parliamentary Budget officer. As we had noted below,

The PBO had previously reported that Canada needs to build another 1.3 million homes by 2030 to close the housing gap — and today it says the revised immigration plan will help but will still result in a housing gap of 658,000 units.

What we find most interesting is how the PBO came to this conclusion. The still large housing gap forecasted in 2030 assumes the housing stock will increase on average by 280,000 units annually. This is higher than their earlier forecast in April. What is the PBO seeing that we aren’t?

Remember, the record high for housing completions totalled 257,243 units back in 1974. So the PBO is suggesting we will set record housing completions, each year, for the next five years and we’ll still have a gap of 658,000 units.

In our view both the PBO and the Trudeau government will be wildly offside on their forecasts. As we have been noting in our writing for some time, housing starts are in the process of falling off cliff, all we need to do is follow the leading indicators.

This week we received more news that further cement our view, the leading indicators in the development space are getting worse- not better.

Big names are circling the drain.

Thind Properties, an established developer in the city of Vancouver has entered into receivership. Several projects now hang in the balance, as does his real estate empire.

As noted in the Vancouver Sun, last year, when Thind earned the Order of B.C., the province’s highest honour, his official biography said he was responsible for $4 billion in development, more than 1,000 jobs throughout Metro Vancouver, and millions in charitable donations.

Thind had successfully completed and sold out 17 multi-family developments over the years, as noted by Altus Group. An impressive track record.

The sudden unwind of Thind is accompanied by over $300M of debt spread out across several projects, according to court claims.

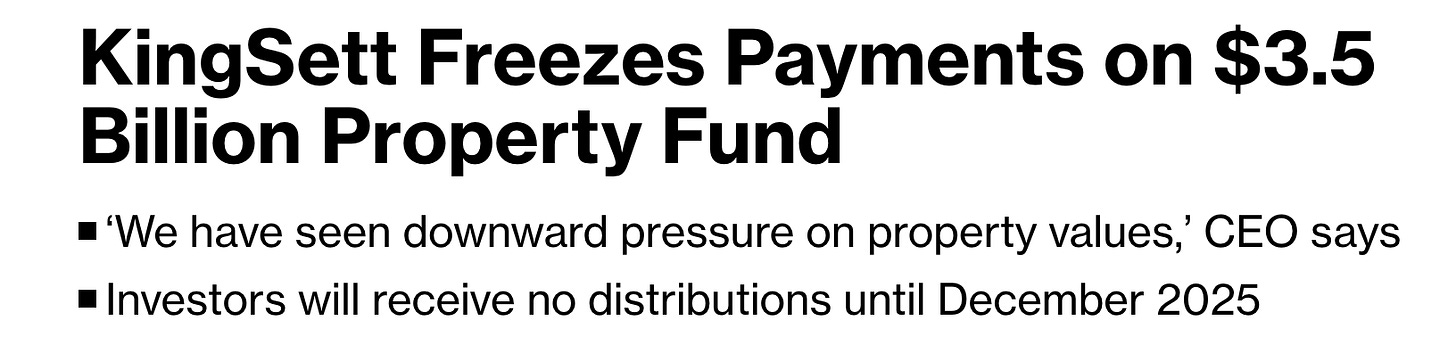

The day after Thind’s struggles went public, Thind’s lender, KingSett Capital, announced it was freezing payments on its $3.5B property fund.

The Toronto-based firm said holders of the KingSett Canadian Real Estate Income Fund won’t get any income distributions for the next year, nor will they be able to redeem their units.

“Unfortunately, we have seen downward pressure on property values and illiquidity in the market,” KingSett Chief Executive Officer Rob Kumer said. “In this environment, the right thing to do is to retain liquidity and fortify our balance sheet so that we are well positioned to generate growth in the recovery that will follow.”

KingSett, i’m sure, will be fine. What’s important here is to focus on the signal. Another major fund has had close the gates in order to prevent capital outflows. First it was Rompsen, now KingSett, and these are just the ones that made it public.

In other words, the name of the game today is capital preservation, not capital appreciation. Money for new developments is getting tighter, not looser, despite the Bank of Canada’s best efforts.

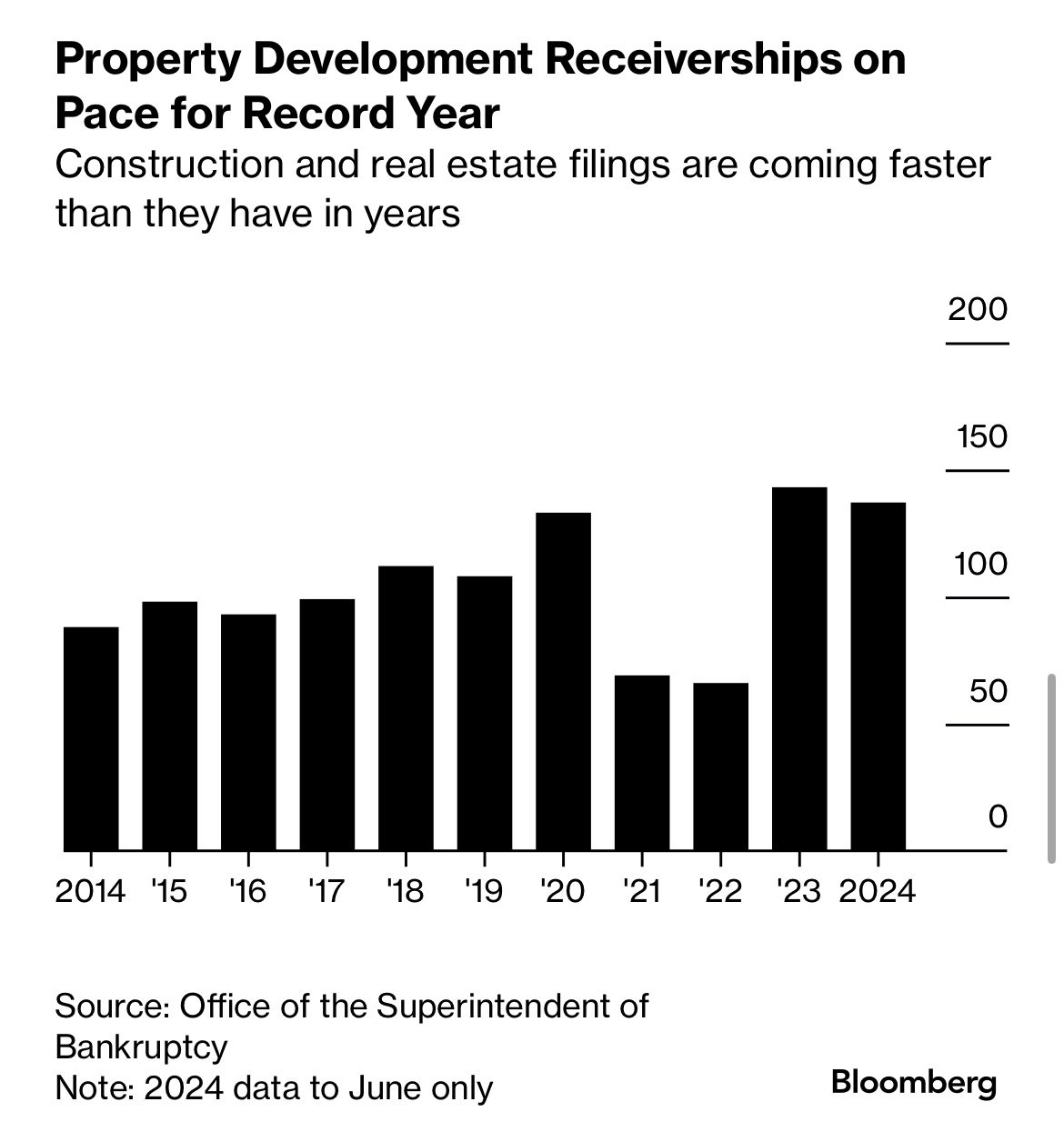

They say cycles are self-correcting, and excesses in one direction lead to excesses in the opposite direction. After a prolonged period of smooth sailing, Real estate developments are going bust at levels not seen in at least a decade.

Unfortunately, the pain is not over yet. Here’s another headline from the Toronto Star this past week.

Sentiment in the development space is downright awful. We continue to believe new housing starts will fall off a cliff in the year ahead and most housing targets will miss by a wide margin, and in the process ending several political careers.

It’s not all bad news though. The weak hands are being shaken out. Bear markets precede bull markets. As the always insightful Howard Marks says, Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism, and die on euphoria.

We are a lot closer to pessimism than euphoria.

“The cure for high prices is high prices”

Excellent summary of the market conditions, Steve. This reminds me of the leaky condo period. Developers used numbered companies to hide from liabilities. In the end, the poor condo owners took the hit.

I wonder if developers are still hiding from liability by this corporate structure? Steve, could you comment on this for us?

Here’s the condo history:

The “leaky condo” crisis in Vancouver refers to a significant construction and financial issue that emerged in the late 1980s and persisted into the early 2000s. During this period, numerous multi-unit condominium buildings in the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island regions suffered extensive damage due to rainwater infiltration. This infiltration led to structural problems such as rot, mold growth, and, in severe cases, compromised structural integrity.

Key Factors Contributing to the Crisis:

1. Design Choices: The adoption of architectural styles suited to drier climates, such as those in California and the Mediterranean, was ill-suited for Vancouver’s wet conditions. Features like minimal roof overhangs and stucco cladding without adequate drainage systems allowed water to penetrate building envelopes.

2. Construction Practices: A construction boom during this era led to rapid development, often at the expense of quality. Some developers and contractors lacked experience with the local climate, resulting in buildings that couldn’t withstand Vancouver’s high rainfall.

3. Regulatory Oversight: Building codes at the time did not adequately address the unique challenges posed by Vancouver’s climate. Additionally, enforcement of existing regulations was often lax, allowing substandard construction practices to go unchecked.

Impact:

By 2003, the British Columbia Homeowner Protection Office had identified approximately 65,000 leaky condos across the province. The financial burden of repairs was substantial, with many homeowners facing costs in the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. The crisis is estimated to have cost the B.C. economy billions of dollars.

Response and Reforms:

In response to the crisis, the provincial government established the Barrett Commission of Inquiry in 1998 to investigate the issue. The commission’s findings led to significant changes in building codes, including the mandatory implementation of rainscreen technology in new constructions to enhance water drainage and prevent future leaks. Additionally, the government introduced interest-free loans to assist affected homeowners with repair costs.

Current Considerations:

While many affected buildings have been repaired, some structures from that era may still have unresolved issues. Prospective buyers are advised to conduct thorough inspections and review building maintenance records to ensure that any past problems have been adequately addressed.

The leaky condo crisis serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of designing and constructing buildings that are well-suited to their environmental conditions, as well as the need for rigorous regulatory oversight to ensure building integrity.